The Bends and Curves Spring Tour 2020 (8 – 15 May) is all about driving the most beautiful roads for sports cars in the Eifel, Black Forest, Vosges and Ardennes. Half way this road trip, a visit of the ‘Cité de l’Automobile’ in Mulhouse is planned. This museum, nicknaming itself ‘the largest car museum in the world’, is better known for its ‘The Schlumpf Collection’. Besides the cars, also the story behind the cars is famous and worth diving in to.

The museum is dedicated to Jeanne Schlumpf, mother of Hans (‘Giovanni’) and Fritz (‘Federico’) Schlumpf. They once were Swiss citizens born in Italy, but after their mother Jeanne was widowed, she moved the family to her home town of Mulhouse in Alsace, France. In 1935 Hans and Fritz started a company that focussed on producing spun woollen products, a business their father had been into in Switzerland before he died. After WWII the keen entrepeneurs made the company a big success and became very wealthy. An interesting article about the the path they walked, seen in the light of that period of time, was written by Paul Wouters (only available in Dutch though).

Fritz Schlumpf was a car enhousiast to say the least. Automotive engineering was his passion and having wanted a Bugatti since childhood, he bought a Bugatti Type 35B just before the German invasion of France.

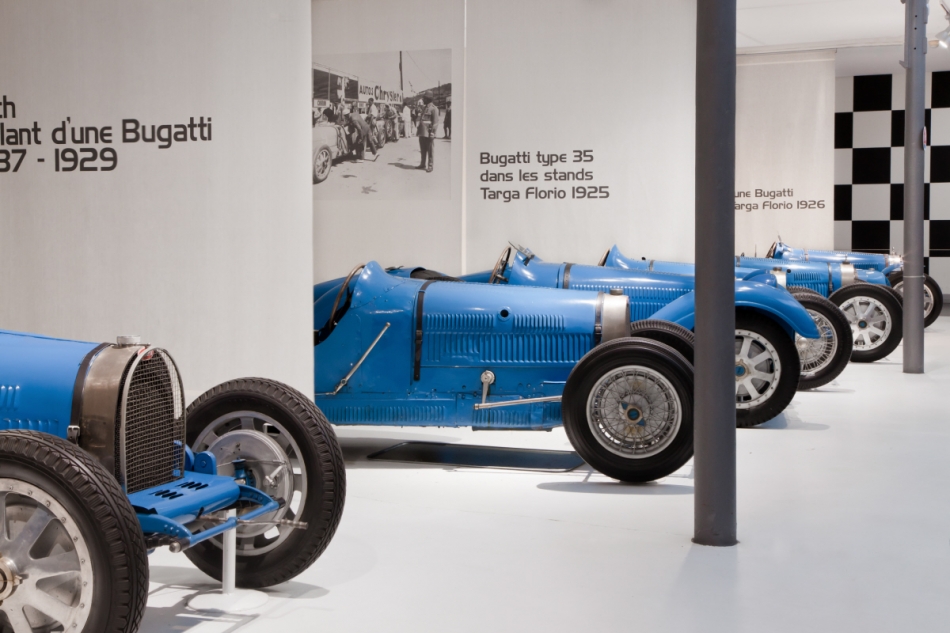

After the war he began racing classic cars, but was requested by the textile union to stop that because of the risks. In stead of racing, Fritz and Hans Schlumpf gathered an enormous collection of nearly 400 classic automobiles and parts of them, including several hundred Bugattis. It was Fritz’ dream to own at least one of every Bugatti type car, the marque that had its roots in the same region as where Jeanne Schlumpf was born and raised and where the family earned its fortune.

In the early 60s the wollen industry was less profitable because of cheaper labour in Asia. From 1964 the company results started to downturn. The Schlumpfs decided to use a wing of the former Mulhouse spinning mill to quietly restore and house the collection. A team of up to 40 carpenters, saddlers, and master mechanics was assembled to carry out the restoration work, who under a confidentiality agreement kept their work and the scale of the collection a secret. Although many, including members of Bugatti clubs around the world, knew of the collection, the scale of the enterprise surprised almost everybody.

Fritz visited Mulhouse daily, choosing the colors and type of restoration each car would receive. The workers removed the mill’s interior walls and laid a red tile walkway with gravel floors for the cars to rest upon. By 1976 the Schlumpf brothers began selling their factories and had to lay off employees. Several strikes broke out and workers broke into the Mulhouse ‘factory’ to find the astounding collection of cars. An unrestored Austin 7 was burned and the workers’ union representative remarked “There are 600 more where this one came from.”

The Schlumpfs fled to their native Switzerland, and spent the rest of their days as permanent residents of the Drei Koenige Hotel in Basel. To recoup some lost wages, the union opened the ‘museum’ to the public, with some 800,000 people viewing the collection in two years.

As the scale of the brothers Schlumpf debt rose, various creditors, including the French government and unions, eyed the car collection toward recovering their losses. To save the collection from destruction, break-up or export the contents were classified in 1978 as a French Historic Monument by Council of State. In 1979, a bankruptcy liquidator ordered the building closed.

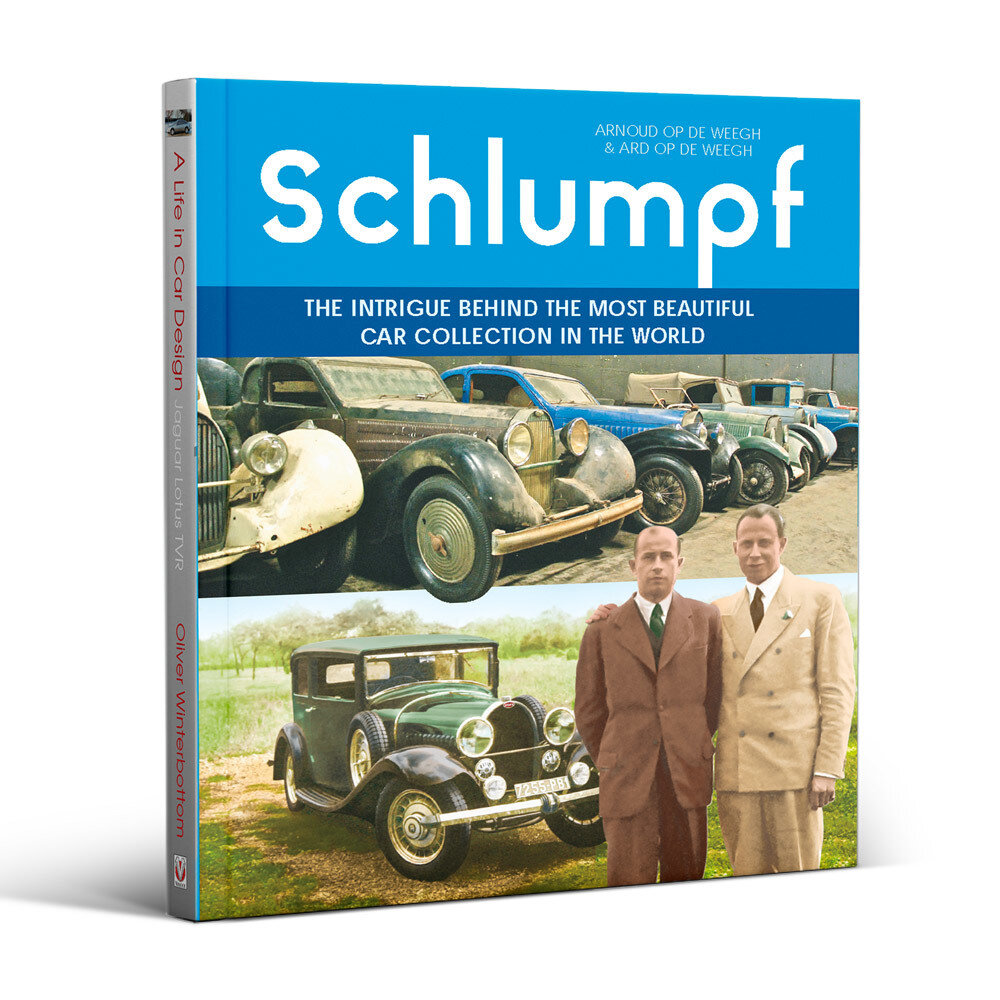

The Schlumpf brothers were accused of fraudulent actions to obtain their collection, but following extensive research by the authors of the book ‘Schlumpf – The intrigue behind the most beautiful car collection in the world’ , a different story is written. Dutch authors Ard and Arnoud op de Weegh, also known for their well received book about other car collections and car cemetaries, spent many years investigating the Schlumpf affair.

They discovered many previously unpublished documents which they say prove that the Schlumpf brothers have been wrongly accused over the years. Furthermore, according to father and son Op de Weegh Fritz Schlumpf tried to save his factories in 1976 by selling (a part of) his collection to Tom Wheatcroft. “There was a witness at the negotiations. The transaction didn’t take place, because the French Government forbid it. Now it seems, that not the Schlumpfs were to blame for the bankrupt, but the French authorities.” They wrote the book “to tell the true story behind the collection, and also to rehabilitate the Schlumpf family”. Order the English translation of the book here or a Dutch copy here.

The current collection at the Cité de l’Automobile museum includes over 520 vehicles, with 400 displayed in three main sections in chronological order. The museum houses three Type 41 “Royale”s: two of the original six Royales plus a replica of the Esder Royale created at the Schlumpf brothers’ workshops from genuine Bugatti spare parts. Don’t expect to find a well balanced collection of cars from a objective car enthousiast point of vue though; Bugattis are the main attraction and furthermore the museum focusses on European car marques. But it most definately is a must see when visiting the Black forest in Germany or the Elzas and Vosges region in France. For the cars and history sake.

General information about the Schlumpf collection was taken from Wikipedia.

No responses yet